Type “ripped paper” into Google and you’ll be delivered almost 65 million results, with the first few pages pretty much solely taken up by Pinterest pics and downloadable ripped paper PNGs. Ok, we got it, the world is pretty into it. And so am I: ever since I can remember, I’ve loved to rip paper.

It probably started when I was teenager, when I got swept up in the joys of collage and scrapbooking. My cheap plastic guillotine, though creating the perfect straight cut necessary for many projects, was never quite as satisfying as folding and tearing with my own two hands.

But what exactly is it about ripping paper which looks and feels so good?

The aesthetic of the rip

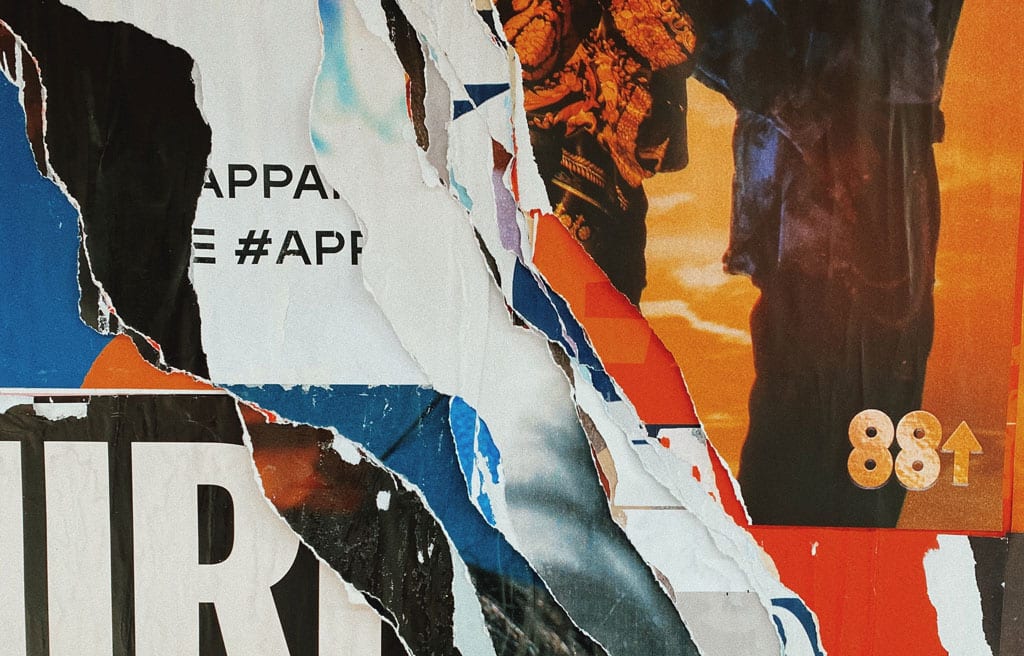

A rip makes a piece of paper’s straight edges more organic. Its smoothness becomes more textured; its flatness, more sculptural. It can look grungy or delicate, angry or tentative, controlled or uncontrolled. There is something wonderful about a straight ripped edge – its roughness so skilfully toes the line between perfection and imperfection. And regardless of whether we’re ripping straight or freestyle, the individual fibres of the paper are revealed. We catch a glimpse of its origins and the way it was made.

It gives us a sense of passing time: the rip makes the paper look aged, worn, damaged. It’s been through the wars, and yet – it still exists. It has survived. Maybe that’s one of the reasons that we’re so drawn to ripped paper. Like us, it is equal parts fragility and strength.

A violent action

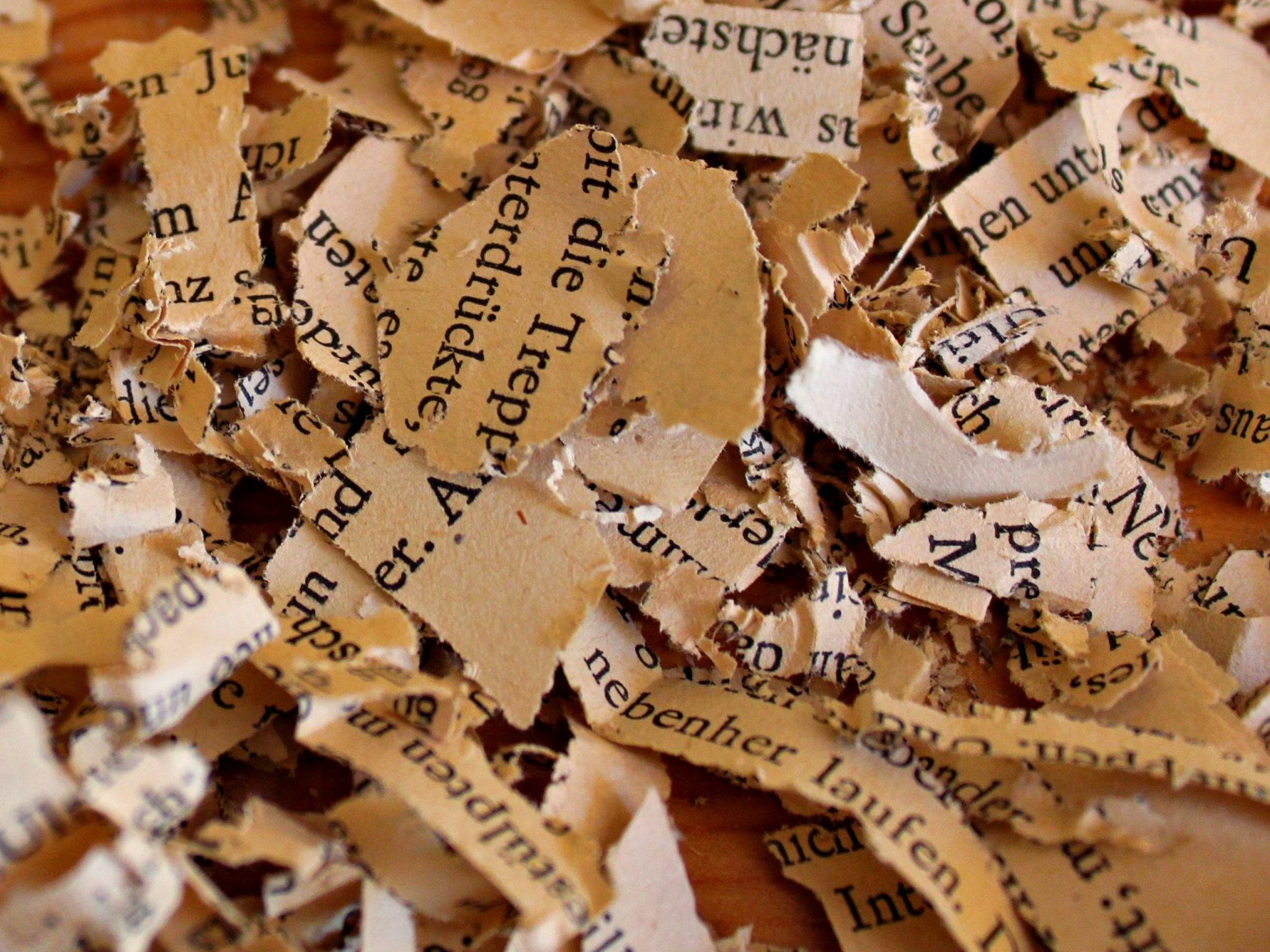

On its surface, ripping is a violent action: an act of destruction through which the original document ceases to exist. Images spring to mind of paperwork being shredded into teeny-tiny pieces, or a letter from an ex-lover being torn up in rage. In the first instance, the purpose might be to conceal the document’s contents, literally pulling words apart from each other so that others can no longer see or make sense of them. In the latter instance, the intent of the wounded lover is to eradicate the letter from their own lives, their own minds – perhaps because its contents were too powerful, painful, or infuriating.

From destruction to creation

I remember being in After School Care at my first primary school, five or six years old. We’d been told to clean up the covered-in area – everyone had to collect ten pieces of rubbish before we were allowed to start playing again. The first piece of rubbish I found was a scrunched up piece of paper. I remember thinking to myself: If I rip this one piece of paper into ten smaller pieces, it will technically make my job here a whole lot easier. Genius, right?

Safe to say, my teacher didn’t think so. But years later, the same principle (ripping paper = creation) is still serving me well.

A couple of years ago I created these large abstract works, watered-down acrylic on paper. Some of them worked. The others, I hated. There were sections which were ok, but the overall composition and rhythm just sucked. I couldn’t look at them.

Weeks later, I got my metal ruler out and ripped them up into sixty-four little colourful rectangles. It was liberating, destroying these shitty paintings. The little cut outs – closeups, stripped of their original context – were bearable. Somehow even nice to look at. I stuck them on card, and they became birthday cards for friends.

A transformative power

So, while ripping paper can be an act of destruction, it is also an act of creation. In ripping something we change its form; we put it through a process of transformation. We generate something new.

And the transformation is not only happening to the paper: something is shifting inside of us, too. When I ripped up my old paintings, I felt the cathartic release of tearing them to shreds – letting them go, and discovering something new in their place. In the case of the wounded lover, ripping the letter up in anger (or frustration, or sadness) actually helps: because it’s letting out energy. It’s an outward acknowledgement of an inner state of being. It moves towards completing our stress response cycle. And basically, it’s damn satisfying.

Now that I reflect on the paper-ripping of my teenage years, I realise that it probably helped me to get out some of that built-up energy. Sure, I may have just been pottering around with colourful paper and making things that looked nice…but it balanced me out. It let me release some of the emotions that I didn’t feel I could express in any other way.

Let a rip

We can rip fast or slow; with tender care or a reckless anger. We can rip the straightest of straight lines with the aid of folds or a book or a ruler; we can rip the beautiful raw edges reminiscent of those ancient peeling posters we saw on the streets in Prague. We can find out how different papers react to our touch, adjusting the speed of the rip or the angle of the downward pull. As I get in tune with my paper, I get in tune with myself.

Ripping paper can be what we want it to be: a way to achieve a desired aesthetic effect or a way to release built up frustration. An act of destruction or an act of creation. Or all of it at once.

But whatever paper-ripping is to each of us, it brings the double bounty:

Looks good. Feels awesome.

Your turn

So here is my gentle invitation to you, whether you want to process some hefty emotions or make something that looks cool:

- Go and grab a bunch of magazines, old books, paper scraps.

- Find some paper that you like the look of (or something you want to get rid of).

- Decide how you want to rip – fold and tear, metal ruler, freestyle, or some other way.

…And then rip it baby. Rip it good.